Debate 101: Argumentation

I - Introduction

Since the Greeks and Romans of ancient times, argumentation has been used. In present times, it has become important in our lives. Each of us has argued at some time or another. Arguing has become a pastime and, for us in the Brotherhood, it is often a necessity. As you already know, arguing can be fun when done well and a curse when done poorly. However, argumentation is a skill of much importance in life as well as within the Brotherhood. This course will give an in-depth look at the process of argumentation.

First, you will learn some of the basic concepts of formal argumentation. The first is the Claim. A claim is a declarative statement or conclusion that is asserted for acceptance. A type of claim that is put forward often is called an Assertion - a statement made without support or reason. The statement "My Clan could win a feud with your Clan" is an assertion because there are no reasons given to prove this point.

The second concept is Contradiction. For this particular topic, contradiction will hold a specific meaning: It is two conflicting claims that are unsupported. For example, the first claim: "My Clan could win a feud with your Clan". The second claim: "No, my Clan is better than yours". These two claims have nothing to validate their worth.

The third concept is the Argument. The definition of argument is 'to have a disagreement, quarrel, dispute'. For a person trained or knowledgeable in argumentation (as you soon will be), this is not an argument. In an argument, a claim is supported by reasons. "My Clan could win a feud with your Clan because we have the ten best gamers" is an argument because the claim is supported by reasons. Now you might say that it is not supported by reasons because only one reason is given, but in fact, two are there.

This brings us to the structure of an argument. Any argument will have a claim along with at least two reasons (premises). In the argument above, the claim is 'My Clan could win a feud with your Clan'. The premise is 'because we have the ten best gamers'. The first reason is supplied by the person hearing the argument and is called the suppressed premise. In this case, it would be “ten highly skilled gamers is a large amount.” Any argument can be broken down this way, in what we call a syllogistic fashion. An argument need not have conflict involved in it to be an argument. Our example could have the other Clan’s member agree with the first, but the first would still have advanced an argument. There need not be a second person at all, as there is no conflict inherent to an argument.

Now we come to the last of the concepts, Debate. A debate is the process of logically evaluating a claim by entertaining arguments for and against the claim, followed by adopting or not adopting the claim as a reasonable resolution to a dispute. Debate requires arguments to be involved, or it is simply contradictory. To return to our example once more, one member stated that his Clan would win on the basis that they have the ten best gamers. The other can state that his Clan would win because there are more events in a feud besides gaming. Now we have a debate taking place.

There are two different points of debate. Public debate focuses on the truth of a resolution. Academic or competitive debate focuses on how well the participants debated for their side of the motion.

II - Debatable Claims

There are many issues to debate about. Some are of a factual nature, some of a value nature, and some of a policy nature. All debates have different requirements of which the advocates and opponents must be aware. This section will give an overview of the requirements attached to these three different types of propositions.

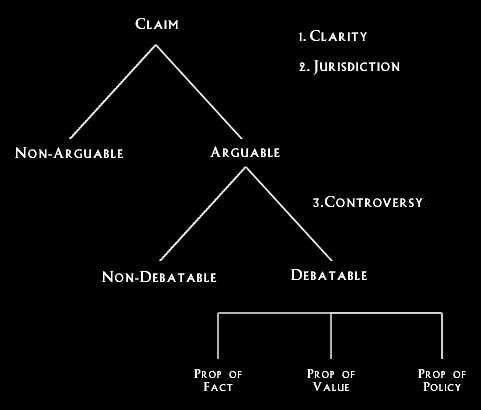

In order to compete in any forum of debate, one must first have a debatable claim. The diagram above is called the Claim Tree. It is a series of criteria that must be fulfilled from the point when a claim is made to the point it may be debated. In order for a claim to be arguable, it must meet the first two requirements: It must have both clarity and jurisdiction of logic.

Clarity simply implies that there must be an agreement between the two parties as to what the resolution means. Debate is a linguistic activity and uses words. Unfortunately, words can have different meanings. Many times there is genuine disagreement over what a word means, but many times one side will find it strategically beneficial to define a term a certain way. In many instances, there will be a debate over the definitions of words, and this is known as a procedural issue. The saying goes that “During a debate, debaters debate about what they are going to debate about so they can then debate about what they want to debate about.” Definitions are important, as they define what are and are not topical issues. Topical issues are arguments that are germane to the resolution under dispute, and non-topical arguments, regardless of importance, are of no value in debate.

The second requirement for a claim is Jurisdiction. Jurisdiction may be defined as the willingness of the parties to submit the claim to logic and presumably abide by the result. The concept of jurisdiction involves two things. First, a claim must be one that is susceptible to analytical argument. If the claim falls outside the boundaries of rational demonstration, it is unarguable. The second part of this applies to the parties involved. They must be willing to think rationally. If one has a closed mind and refuses to listen to reason, then jurisdiction is not being granted. Meeting clarity and jurisdiction gives you an arguable claim, but one more level is needed before it is a debatable claim.

The third requirement is Controversy. A claim is not debatable if no reasonable person could hold a contrary position. Debate assumes that there will be a clash of opposites. Obviously, if there are no opposites, there is no debate. The process of debate demands that there be at least two sides. These sides might be created artificially by a devil’s advocate or by a genuinely held contrary position, but if there is no opposition, there can be no debate. This brings us to the three kinds of debatable claims, or propositions: factual, value, and policy.

First, we will discuss fact. Factual issues are any objective statements. They are possible to prove with empirical evidence. This doesn’t mean that the empirical evidence can be found, but if it were present, it would prove the proposition. An example of this would be, “Resolved: that the Empire’s judicial system did not put enough emphasis on the rights of the accused.” Now, this may seem like a value debate, but the resolution never stated that this was harmful or beneficial, just that it was. The stock issues in a factual debate are definitions, evidence, and inference. You must define what the terms of the resolution mean, define what evidence you have to support it, and have some kind of inference made from it. You could define “enough” as the amount equal to the court system of Alderaan. Then, you would give evidence that that level of emphasis was not given. Then, the fact that not enough was given would be inferred.

The second type of proposition is a value proposition. A value proposition is something of a subjective nature and cannot be proven with empirical evidence. A value proposition will likely contain words such as better, worse, unjustified, etc. The stock issue of this debate is a value criterion. The value criterion is the prism through which the various arguments and contentions will be weighed in the debate.

The final type of proposition is one of policy. A policy proposition must have two major parts: An agent and an action. One theoretical example would be: “Resolved: the Dark Jedi Brotherhood should increase member activity.” The agent would be the DJB, and the action would be some method of increasing activity. There are four things that a policy argument must have. The first is harms. This is simply something that the status quo is doing that is wrong. For this argument, one harm might be that low activity is detrimental to the Brotherhood and could cause the group to collapse. The second part of this is inherency, which involves showing how the status quo is incapable of solving the problem. Here, the inherency could be that the current competition structure has not and cannot promote high enough levels of activity. The third element is a plan. The plan is what you would do to cure the problem. One plan for this problem would be to have the Clan leaders hold more feuds. To have a complete plan, one must have an agent of action, an agent of enforcement, and a means of addressing the costs. (Note: The cost does not simply mean money, anything that is needed to complete the plan would be covered here. This could be time, resources, effort, etc.) Here, the agent of action would be the Clan leaders, the agent of enforcement could be the Dark Council of the DJB, and the cost would be whoever’s time that would be used running the feuds and setting them up. The fourth and final piece is solvency. Any plan must have a means to solve the problem. Saying that it “just will” isn’t acceptable. For this example, stating that this plan would solve our harm because people tend to participate more and become more involved in Feuds where Clan prestige is on the line than in regular, run-of-the-mill competitions. A policy debate must also have a criterion, most often net benefits, with which to judge whether the plan is viable.

Any successful case made for any of these three types of propositions must be what is called a prima-facie case. This is a case which, without refutation, would convince a reasonable person to adopt the resolution.

III - Assignments in Debate

There are four interrelated factors in any debate: The presumption, burden of proof, burden of clash, and standard of proof. Together, they may be spoken of as the assignments of the debate, as they tell the affirmative and negative what they must do. An argument is won when the party with the burden of proof meets the standard of proof and overcomes presumption. Thus, the concepts of burdens, presumptions, and standards are closely related. The burden answers the question of who has the task of proving an issue, presumption rests automatically with the party that doesn’t have the burden, and the standard is the degree of certainty to which the claim must be proven.

Presumption is the first thing to assign in any debate, and it is intrinsic to the phrasing of the resolution itself. The first step is to analyze the resolution to determine where the status quo lies. The status quo is best defined as “the way things are now” or “the existing state of things.” The presumption should always lie with the negative, as the affirmative is held to the burden of changing our minds. As such, a resolution should always be advocating for a change as opposed to maintaining the status quo so as to place the presumption with the negative. An example of a proper placement would be: “Resolved: that Clans should hold weekly meetings on IRC.” The presumption is given to the negative here because if you do not adopt the resolution, the status quo is maintained.

The Burden of Proof is the reverse of enjoying presumption, and it is a burden to establish good reasons for adopting the resolution. This is shown through one of the most elementary rules of debate: “The party which asserts a claim must prove it.” At the start of the debate, the affirmative asserts a resolution. Therefore, by the end of the debate, the affirmative must prove the resolution, or it will lose the debate. Also, while the affirmative has the burden of proof, both the affirmative and negative have a burden to prove their specific claims. However, clearly when the debate begins, only the affirmative has a burden of proof. They must substantiate the specific claims they put forward as justification for adoption of the resolution. Theoretically, the negative doesn’t have a burden of proof which they must meet, as they don’t have to put forward any arguments. If, after hearing the affirmative argumentation in favor of a resolution, the critic is not convinced, then it is a de facto negative win. Using the above example, if the affirmative does not convince the critic that weekly meetings should be instituted, they would lose the debate even if the negative said nothing.

In competitive debate, however, the negative cannot simply rest on its presumption and await victory. Once the party with the burden of proof has set forth its argument, the opposing party must respond to the argument, or it is considered granted. The burden of clash is the burden to respond to the opponent’s arguments or grant it through silence. This burden of response or “clash” grows out of one of the oldest principles of argumentation: “Silence means consent.” If an argument is not addressed, then the argument is conceded as true. Using the previous example of weekly meetings, the affirmative might argue that the Brotherhood had held weekly meetings previously with good results. If the negative fails to address that (by perhaps saying that times have changed and the weekly formal meeting is no longer as beneficial), then they essentially grant the validity of that argument.

The last assignment is the standard of proof, or the degree of certainty to which the claim must be proven in order to warrant its adoption by the judicator. Common standards of proof are possibility, plausibility, probability, and certainty. Possibility is the lowest standard and the easiest to uphold. Basically, it means that if something can happen, no matter the odds of likelihood, it is possible. Plausibility suggests that the claim has a relatively good chance of being true, but one that is still less than likely to be true. Probability states that the claim will be more likely true than not. The fourth standard, certainty, is expressed in criminal case law as proof “beyond a reasonable doubt”. Believing something as a certainty is a conviction in which we would have considerable faith. In the Dark Brotherhood, the most commonly used standard of proof is probability, otherwise known as “preponderance of the evidence”. This standard is not only used in competitive Brotherhood debate formats, but is also that which is used for juries in the Chamber of Justice.

IV - Types of Arguments

Here is a list of most of the different arguments that one can put together in debate. Each type of argument also has questions that must be answered to find if it is a correct argument.

Testimony Argument: an argument that uses the testimonial conclusion of another person as its support.

- Is the source an expert?

- Is the source unbiased?

- Is support available?

Causal Argument: suggests that some instance or event forces, gives rise to, or helps produce a particular effect.

- Does the alleged cause precede the effect?

- Is the cause relevant to the effect?

- Is the cause an inherent fact in producing the effect?

- Can other possible causal explanations be ruled out?

Example Argument: an argument that examines the instances within a given classification or population in order to find the patterns or similarities within the grouping.

- Are the examples relevant to the claim?

- Are there a sufficient number of examples?

- Are the examples typical?

- Are counter examples insignificant?

Analogy Argument: Making a comparison between two similar cases and inferring that what is true in one case is true in another.

- Are only literal (instead of figurative) analogies used?

- Are the instances similar in significant detail?

- Are the differences non-critical?

Sign Argument: Inferring relationships or correlation between two variables. This means that one sign is given, and a conclusion is reached based on this through reasoning. One such example would be: if upon signing on to Telegram following the conclusion of a Great Jedi War, you saw people congratulating a particular Clan, you would then reason, through inference, that said Clan had likely won the War even though you had not seen the scores released yet.

- Is the known variable relevant to the unknown variable?

- Is the sign relationship inherent?

- Are other signs that reinforce the initial sign present?

Statistics: The use of numbers; conclusions to studies, results of opinion polls, or total number of people or objects within a certain classification.

- Are the statistics descriptive or inferential? A descriptive statistic is one where you are looking at the entirety of a given classification. An example would be saying that 80% of the Dark Council are of the Sith Order. You would check the entire Dark Council and see how many Sith there are. An inferential statistic, on the other hand, takes a small cross section of the grouping to try to create a picture of the whole. Here, if you were to poll 40 members and found that 90% of them favored holding feud events more often, you could infer that most of the Brotherhood would hold that opinion.

For inferential statistics: * Is a representative sample collected? * Is the sample size adequate? * Is the questioning technique appropriate? * Is either under or over representation a concern? (For example, all your surveyed people are from one group) * What is the average utilized? (Mean, Median, or Mode)

Argument by Definition: determining whether something should be included within the realm of a particular definition or classification.

- Is the definition clear?

- Is the definition the accepted definition?

- Does the phenomenon fit within the definition?

Please log in to take this course's exam